Like many of you, I’ve been struggling to interpret what has been occurring in Ukraine since Russia invaded on February 24, 2022. This action is a violation of international law and is bringing death and destruction to Ukrainian civilians. I condemn Russia’s action unreservedly. Russia’s action cannot be excused or rationalized away. However, it can’t be understood without recognizing that the roots of this conflict go back at least 30 years, and the US has played an important role in the tragedy.

Friends trying to interpret the recent news have asked for resources that might add some missing context or balance to the mainstream news coverage. I thought it might be useful for me to post the various materials I’ve recommended. Note that I am sharing resources aiming to complement the information contained in mainstream coverage, which consistently supports the elite-promoted narratives and interpretations of what is going on. And, of course, the elite coalition has further intensified the scope and intensity of censorship since the invasion began – so the likelihood of hearing alternative views is ever lower.

The most critical events that have been airbrushed out of the Western media’s coverage and narratives related to the current Ukraine-Russia crisis are:

– the violation of agreements Western leaders made at the end of the Cold War not to expand NATO into Eastern Europe (note that many esteemed US foreign policy practitioners and experts warned that the policy was unwise and would provoke conflict with Russia;

-the failure to establish and institutionalize security relationships within Europe that can account for Russia’s security concerns; and,

-the transformation of NATO from a defensive alliance into…a different kind of security organization (e.g. one which bombed Serbia in 1999, and destroyed the Libyan state in 2011, among other things);

– the shift to a more aggressive posture toward Russia signaled by, inter alia, the US exiting treaties designed to contain weapons proliferation e.g. ABM treaty, installing new “defensive” weapons systems, as well as the waves of sanctions targeting Russia;

– the U.S.-backed coup in Ukraine in February 2014;

-the efforts to blame the Government of Russia for the downing (July 2014) of flight MH17 and to ensure the crash investigation did not exonerate the Russia government and attribute blame to Ukrainian forces (see brief description from Robert Parry in 2017);

– the role of far-right political operatives & neo-Nazi militias in the 2014 coup, and in the post-coup government, including their engagement in violence in eastern Ukraine. They have formed new “National Guard” units engaged in the assaults on the separatist People’s Republics. Source. Aaron Mate 2022, also Robert Parry 2014.

– the fact that Maidan (pro-coup) forces engaged in mass killing during the 2014 coup, and that a sustained effort has been made to keep this fact from becoming known by the public. See Katchanovski 2020.

-the fact that the Trump administration reversed the Obama administration’s position and provided $39M in lethal weapons to Ukraine in October 2019.

-the fact that on February 19, 2022, Ukraine’s president Zelinsky said that Ukraine might pursue nuclear weapons.

Useful recent references giving broader background on US-Russia-Ukraine relations pertinent to current crisis.

Horton, Scott. Feb 26 2022. Speech on the History Behind the Russia-Ukraine Crisis SLC, Utah. Video approx 2 hrs.

Mate, Aaron. March 3 2022. By using Ukraine to fight Russia, the US provoked Putin’s war

“After backing a far-right coup in 2014, the US has fueled a proxy war in eastern Ukraine that has left 14,000 dead. Russia’s invasion is an illegal and catastrophic response.”

Richard Sakwa interview on Jerm Warfare podcast, March 6, 2020, audio, approx 1.5 hours.

Medea Benjamin, Nicolas J. S. Davies, Feb 2 2022. US Reaping What It Sowed in Ukraine. This reference covers the important role Vice President Biden played in the 2014 coup operation.

Coincidentally, a dear old friend of mine, Amy Boone, has responded to a similar query by writing a wonderful article on this topic. I am amazed at how similar our perspectives are, given our backgrounds and personalities are quite different. We do share the experience of having spent many years studying the Soviet Union/Russia and then having spent time living there in the 1990s. Here is her February 7, 2022 piece: Everything You Always Wanted to Know about Ukraine.

I recently watched the 2017 documentary “Ukraine on Fire” and found it well worth watching, in particular for the presentation of the history of the far-right and neo-Nazi groups operating in Ukraine today, as well as examination of the (considerable!) evidence that a USG-sponsored regime change operation was behind the 2014 coup which forced Yanukovych from power. Oliver Stone was an executive producer of the film. Here’s a worthwhile piece on the film from Consortium News. I gather YouTube recently removed the film. You can watch it on Rumble however.

In case anyone gets super intrigued and wants to read a book on this topic, I highly recommend Richard Sakwa’s 2014 book Frontline Ukraine: Crisis in the Borderlands. A good book review from 2015.

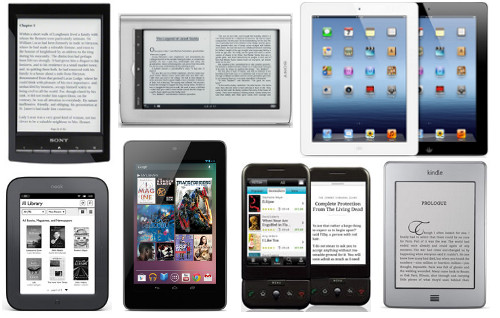

Once you do this, you can browse your library’s collection, and check out or place a hold on the book of your choice. If you have a Kindle e-reader, you need to link to your Amazon account and then checked-out books will show up in the same place as Amazon purchased books, including on your Kindle (

Once you do this, you can browse your library’s collection, and check out or place a hold on the book of your choice. If you have a Kindle e-reader, you need to link to your Amazon account and then checked-out books will show up in the same place as Amazon purchased books, including on your Kindle (